“Dimmi come abiti e ti dirò chi sei”.“

Mario Praz, Filosofia dell’Arredamento

Così tante volte mi sono trovata a visitare il museo Mario Praz che quando passo in via Zanardelli n°1, proprio dietro Piazza Navona, è quasi d’obbligo entrare. Una delle poche case museo a Roma, forse l’unica con questo gusto ottocentesco, inaspettata tra il barocco totalizzante della città dei papi.

La casa rispecchia perfettamente l’animo del suo proprietario, il professore di letteratura inglese Mario Praz morto nel 1982, il quale disse: “Questo, e non altro, è, nella sua ragione più profonda, la casa: una proiezione dell’io”. Grande anglista, critico e saggista, appassionato di temi macabri, letteratura nera, arredamento, studioso del gusto e collezionista di oggetti del periodo tardo neoclassico e inizi ottocento, con una particolare attrazione per i diorama e i ritratti in cera. La cera, diceva, è quanto di più simile alla pelle umana.

Potrei parlare moltissimo di Mario Praz, uno dei personaggi che più hanno influenzato la mia visione delle cose, ma voglio limitarmi a parlare della sua casa. Più volte il museo è stato a rischio di chiusura, di cui l’ultima recentemente, e per questo mi sono sentita di parlarne adesso. Come tutti i musei minori non si trova nelle guide turistiche, ma proprio per questo si mette al riparo da visitatori casuali e annoiati. Un museo unico da preservare assolutamente e che può rivaleggiare, secondo me, per lo meno per singolarità del collezionista, con il Vittoriale di d’Annunzio o la casa di Gustave Moreau a Parigi. Una casa non grandissima eppure piena di oggetti (più di 1200) che il Professore ha collezionato durante tutta la sua vita. Ogni oggetto è stato scelto per una specifica ragione, alcuni perché gli ricordavano altri oggetti, altri perché ne avevano gli stessi colori, poi simboli, rimandi, tutto è collegato e gli oggetti si parlano rendendo così viva la casa, “La Casa della Vita” infatti è il titolo di uno dei suoi libri.

Sarà per la particolarità della tipologia museale, che in Italia e soprattutto a Roma non è così diffusa, sarà anche per la fama di jettatore che si dice giri intorno a Mario Praz, questa casa continua ad essere un museo di nicchia, così come gli studi di Praz rimangono relegati tra gli specialisti, pochi appassionati. Una figura che rimane ai margini, nonostante la rilevante importanza dei suoi studi, che confinano con la moda, con il gusto e con il macabro e per questo forse più apprezzati all’estero che in Italia. Luchino Visconti fu uno dei primi ad apprezzarlo pubblicamente e a lui si ispirò per il film “Gruppo di famiglia in un interno”. Ma questa è un’altra storia.

La casa

La collezione fu acquistata dalla Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Roma dagli eredi pochi anni dopo la morte del professore, avvenuta nel 1986, e la casa fu aperta come museo nel 1995. La raccolta fu catalogata e sistemata nell’appartamento in modo da ricostruire nel modo più fedele possibile la sistemazione decisa dal proprietario. L’appartamento si compone di nove stanze ed è situato al terzo piano di Palazzo Primoli dove il Professore si trasferì nel 1969, dopo aver lasciato il grande appartamento di palazzo Ricci in Via Giulia, dove aveva abitato con la moglie a partire dal 1934.

Nella sua celebre autobiografia del 1958, La Casa della Vita, ampliata e ripubblicata nel 1979, Mario Praz descrive i diversi ambienti, le stanze della sua casa, intrecciando la storia della sua vita e della sua collezione: dai primi mobili acquistati quando ancora viveva e studiava a Firenze, per passare poi agli oggetti comprati in Inghilterra dove insegnava italiano all’Università, prima a Liverpool e poi a Manchester, fino al trasferimento definitivo a Roma dove dal 1934 era divenuto titolare della Cattedra di Lingua e Letteratura inglese alla Sapienza, e dove sarebbe divenuto notissimo tra gli antiquari romani, quasi quotidianamente visitati.

Numerosi viaggi di studio e di lavoro, compiuti dal collezionista in Austria, Francia, Germania e nel nord dell’Europa, sono stati occasione per ulteriori acquisti e hanno contribuito a definire il carattere europeo della raccolta, con i suoi mobili inglesi, i suoi bronzi francesi, le malachiti provenienti dalla Russia, i cristalli boemi, le porcellane tedesche, le vedute di tante città italiane ed europee, i ritratti delle famiglie regnanti, dai Borbone ai Bonaparte, e quelli di tanti sconosciuti individui vissuti nel XIX secolo.

Mario Praz house museum pt II

Official site: museopraz.beniculturali.it (da cui ho preso la descrizione delle stanze)

Official facebook: Museo Mario Praz

Thanks Eric Pyle for the translation!

Grazie a Antonio Caterino.

***

“Tell me how you live and I’ll tell you who you are.”

Mario Praz, the Philosophy of Furniture

Many times I have found myself visiting the Mario Praz Museum. Every time I pass by Zanardelli No. 1, just behind Piazza Navona, I feel that I really must go in. One of the few house museums in Rome, and perhaps the only one with this nineteenth-century taste, it remains an unexpected sight in the overwhelmingly baroque City of Popes.

The house perfectly reflects the mood of its owner, a professor of English literature. Mario Praz, who died in 1982, said: “The house is, in the deepest sense, a projection of the self.” Praz was a great Anglophile, a critic and essayist. He was fond of macabre themes, dark literature and furniture. He was a scholar and collector with a taste for the late classical period and the early nineteenth century, with a particular attraction to dioramas and portraits in wax. Wax, he said, is most similar to human skin.

I could say a lot about Mario Praz, one of the characters who have most influenced my view of things, but here I want to limit myself to talking about his home. Several times the museum has been threatened with closure, the last time only recently. For this reason I feel like talking about it now. Like all smaller museums not found in the guide books, here one can get away from casual visitors. This is a unique museum to be preserved, that absolutely rivals, in my opinion, at least for the unique taste of the collector, the Vittoriale of D’Annunzio or the home of Gustave Moreau in Paris. The house is not huge, yet it is full of objects (more than 1200) that the Professor collected throughout his life. Each object was chosen for a specific reason; some because they reminded him of other objects in the collection, because they had the same colors, symbols, or references. Everything here is connected, and the objects speak together in the house, bringing the collection and the house to life. The House of Life is the title of one of his books.

Because this is an unusual type of museum in Italy, especially in Rome, and because of the jinxed reputation around Mario Praz, this house remains a niche museum, just as the study of Praz remains popular only among specialists. He is a figure that remains on the sidelines, despite the great importance of his studies, not quite in fashion, with a taste for the macabre and, because of that, perhaps more appreciated abroad than in Italy. Luchino Visconti was one of the first to appreciate Praz’s work publicly; he was inspired by it to make the movie “Conversation Piece.” But that’s another story.

The House

The collection was purchased by the Gallery of Modern Art in Rome from Praz’s heirs a few years after the death of Professor in 1986. The house was opened as a museum in 1995. The collection was cataloged and arranged in the rooms to reconstruct as closely as possible the arrangement made originally by the owner. The apartment consists of nine rooms located on the third floor of the Palazzo Primoli, where the Professor moved in 1969, after leaving the large apartment building in Via Giulia Ricci, where he had lived with his wife since 1934.

In his famous 1958 autobiography, The House of Life, expanded and republished in 1979, Mario Praz describes the different environments in the rooms of his house, weaving together the story of his life and of his collection. He begins with the first furniture bought when he was still living and studying in Florence, and moves on to the objects bought in England where he taught Italian at university, first in Liverpool and then Manchester, until his final return to Rome, where in 1934 he became Professor of English Language and Literature at La Sapienza. He describes how he became well-known among antique dealers, visiting almost daily.

A number of trips for research and work the collector made to Austria, France, Germany and northern Europe, were the occasions for further purchases, and helped to define the European character of the collection, with its English furniture, French bronzes, Russian malachite, Bohemian crystal, German porcelain, views of Italian and European cities, portraits of the ruling families from Bourbon to Bonaparte, and of so many unknown nineteenth century individuals.

Ingresso:

E’ l’unica sala dove, oltre agli oggetti ottocenteschi, ci sono dipinti di artisti contemporanei e amici del professore quali Leonor Fini, Fabrizio Clerici, Stanislao Lepri e Colette Rosselli. In alto a sinistra della porta d’entrata si può vedere il primo di una serie di ritratti di Praz, qui raffigurato ancora abbastanza giovane da Leonetta Cecchi Pieraccini (moglie di Emilio Cecchi e madre di Dario Cecchi e Suso Cecchi d’Amico) allieva del macchiaiolo Giovanni Fattori. La libreria, sulla stessa parete, apparteneva a d’Annunzio e proviene dalla Capponcina.

***

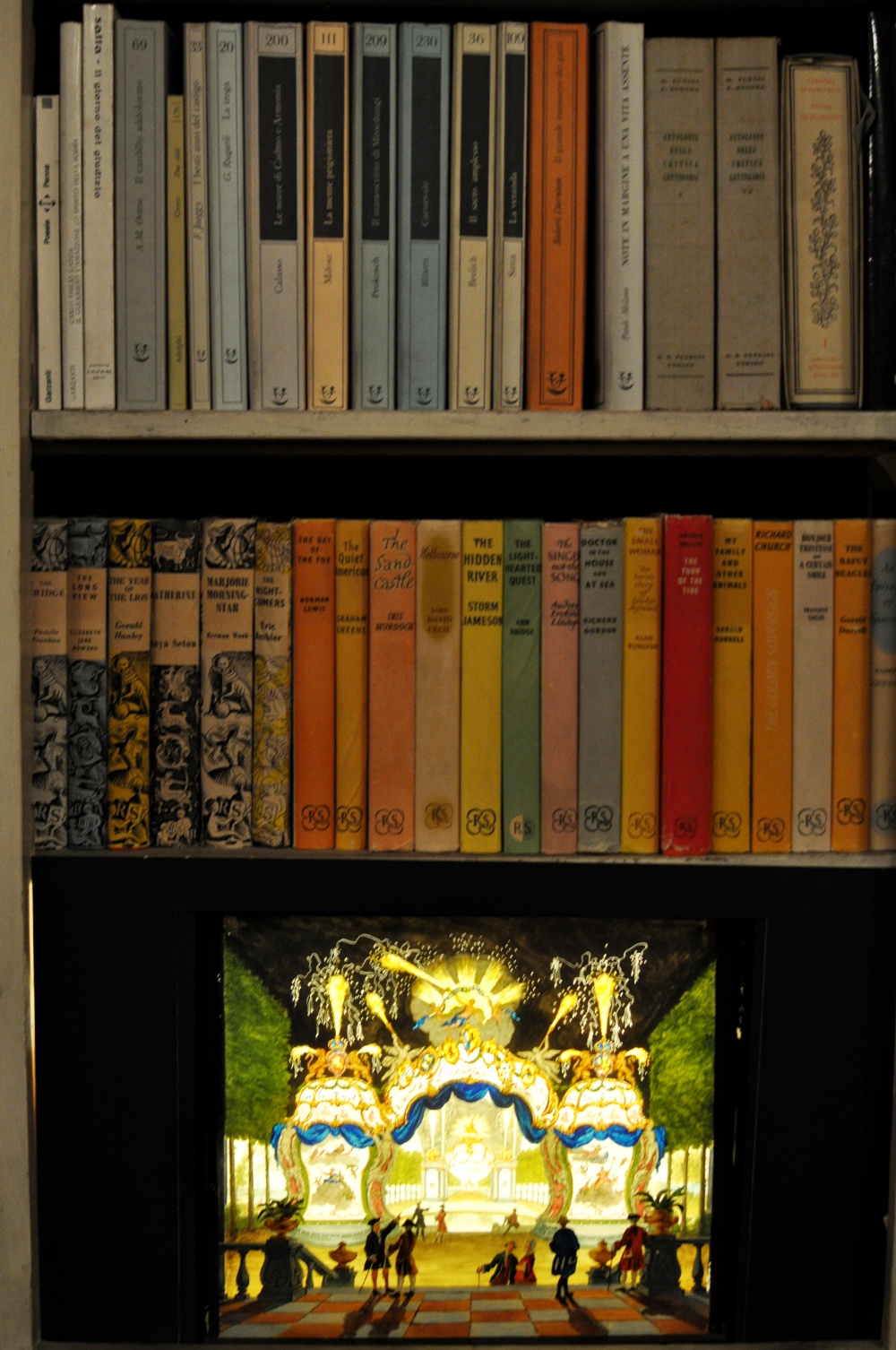

Entrance

It’s the only room which contains objects from the nineteenth century, there are paintings by contemporary artists and friends such as Leonor Fini, Fabrizio Clerici, Stanislao Lepri, and Colette Rosselli. At the top left of the entrance you can see the first of a series of portraits of Praz, still young in a painting by Leonetta Cecchi Pieraccini (wife of Emilio Cecchi and mother of Dario Cecchi and Suso Cecchi d’Amico), a student of Giovanni Fattori. The bookcase on the same wall belonged to D’Annunzio and comes from Capponcina.

Mario Praz ritratto da Leonetta Cecchi Pieraccini

Portrait of Mario Praz by Leonetta Cecchi Pieraccini

al centro un dipinto di Fabrizio Clerici

Center: painting by Fabrizio Clerici

a sinistra: Sfinge di Leonor Fini

Left: Sphinx by Leonor Fini

libreria di Gabriele d’Annunzio

Bookcase of Gabriele d’Annunzio

Salotto:

Il salotto o galleria è caratterizzato dal bianco e dall’oro, accostamento di colori tipicamente neoclassico: a partire dal soffitto a cassettoni, per continuare con i due camini posti simmetricamente ai lati della grande libreria-alcova, e ancora con le poltrone, i divani e le tende.

L’accostamento di questi colori non è casuale e lo ritroviamo nel dipinto di un interno (uno dei tanti che affollano le pareti di casa Praz) che si trova nella parete a sinistra appena si entra. Raffigura Maria Isabella di Napoli nel suo appartamento nel Casino della Regina a Capodimonte , datato 1836 ed opera di Vincenzo Abbati (1803-1866). Guardando al suo interno ci scopriremo a osservare, come in un gioco di specchi, un salone arredato con lo stesso gusto ed analoghi oggetti di quello in cui ci troviamo. Il Professore era solito fare queste cose, scoprire rimandi tra gli oggetti, simbologie e riprese tematiche così che la casa si configura come una specie di gioco per l’osservatore attento e interessato. Per esempio sulla parete di fronte all’ingresso campeggia, su un alto basamento, una statua grande al vero che rappresenta “Amore in caccia “, una scultura in marmo bianco attribuita ad Adamo Tadolini (1788-1868) allievo del Canova. Ritroveremo il tema dell’arco nell’ultima stanza, un arco spezzato però, simbolo della fine della visita e anche della vita.

Spicca alla vista la libreria-alcova: il divano è stato ricamato dallo stesso Mario Praz, che era un appassionato ricamatore, al di sopra invece si può vedere il ritratto fotografico di sua madre, la contessa Giulia Testa, del famoso fotografo Mario Nunes Vais.

Tra le grandi finestre che si aprono sulla parete di destra si alternano alcuni busti femminili: la Marchesa d’Elci con una complicata acconciatura detta en giraffe, Elisa Bonaparte ritratta dal Bartolini (1777-1850) e la raffinata terracotta di Chinard (1756- 1813) raffigurante la giovane Madame de l’Horme.

***

Living room

The living room or gallery is decorated in black and gold, a typically neoclassical color scheme, from the coffered ceiling to the two chimneys placed symmetrically on either side of the alcove with the larger bookcase, as well as the armchairs, sofas, and curtains.

The combination of these colors was not chosen at random: we find them in the painting of an interior (one of many that line the walls of the house) located on the wall to the left as you enter. It depicts Mary Isabella of Naples in her apartment in the Casino Queen in Capodimonte, dated 1836, by Vincenzo Abbati (1803-1866). Looking into the painting we observe, as in a hall of mirrors, a hall decorated in the same style, and with similar objects, as the room in which we find ourselves. The Professor was wont to do these things, finding references among objects, symbols and themes taken to make the house appear as a kind of game for the careful observer. For example, on a high pedestal opposite the entrance stands a life-size marble statue representing “Love in the hunt,” attributed to Adam Tadolini (1788-1868) a pupil of Canova. We will find this theme repeated in the last room, a symbol of the end of the visit, and also of life.

Looking toward the library-alcove, we can see the sofa embroidered by Praz himself, who was an avid embroiderer, and above that the photographic portrait of his mother, the Countess Giulia Testa, by famous photographer Mario Nunes Vais.

Among the large windows on the right wall alternate female busts: the Marquise d’Elci with a complicated hairstyle called “en giraffe,” Elisa Bonaparte portrayed by Bartolini (1777-1850), and an earthenware portrait of the young Madame de Horme by Chinard (1756- 1813).

Maria Isabella di Napoli nel suo appartamento nel Casino della Regina a Capodimonte , di Vincenzo Abbati, 1836

Maria Isabella of Naples in her apartment in the Casino Queen in Capodimonte, Vincenzo Abbots, 1836

Marchesa d’Elci con un’acconciatura detta en giraffe

Marquise d’Elci with a hairstyle called “en giraffe”

divano ricamato da Mario Praz

Sofa embroidered by Mario Praz

“Amore in caccia “attribuita ad Adamo Tadolini, allievo di Canova

“Love in the hunt” attributed to Adamo Tadolini, a pupil of Canova

Studio:

Dalla galleria si può accedere a due stanze, a sinistra si va nella biblioteca, a destra nello studio. Il passaggio verso lo studio è sottolineato dal mutamento dei colori: dal bianco e oro si passa alla predominanza del verde delle pareti, abbinato al rosso delle tende.

Un elemento di continuità tra i due ambienti è invece dato dal lungo soppalco, una struttura ideata dall’architetto Lizzani e dallo stesso Praz per ospitare parte della vastissima biblioteca del professore. E’ possibile accedervi attraverso una scala che parte dallo studio, sormontata da soggetti militari, sciabole e strumenti musicali terminanti in fantastiche teste di draghi. Ai piedi della scala troviamo un dipinto che raffigura il gran Salone di Palazzo Ricci dove Praz aveva abitato per oltre trenta anni prima di trasferirsi a Palazzo Primoli. E’ un’opera di Sergio De Francisco, dipinta nel 1965 ed è interessante notare che molti degli oggetti raffigurati si ritrovano in questa stanza, come la scrivania o il tavolo al centro, come pure negli altri ambienti della casa. Lo stesso Sergio De Francisco è l’autore del ritratto di Praz appeso alla parete dello studio, a sinistra appena si entra.

Al di sotto del ballatoio troviamo, tra alcune Scene di conversazione, quel che si potrebbe definire “una collezione nella collezione”: numerosissime immagini di cera, martiri e santi, nobili e guerrieri, regine e principesse, placchette classicheggianti e coppie di ritratti, databili tra il XVI ed il XIX secolo, che interrompono per un momento il rigoroso limite cronologico a cui l’arredo della casa si attiene. Le cere appassionavano il Professore per l’estrema resa realistica ed insieme quasi morbosa della materia, nel suo invecchiare e disfarsi; oltre settanta di questi oggetti sono disseminati nella casa ma in questo ambiente si trova raccolto il nucleo più numeroso.

Sulla parete alle spalle della scrivania, un bel mobile francese ornato di bronzi, è allestita una vera e propria quadreria con nove dipinti, in basso tre paesaggi italiani, nella fila centrali tre ritratti: il primo quello notissimo che il francese François-Xavier Fabre (1766-1837) fece al Foscolo durante il suo soggiorno fiorentino, di cui sono note diverse versioni; il secondo quello di Teresa Pikler, moglie del Monti, nel giardino del Lago a Villa Borghese, eseguito da Carlo Labruzzi (1747-1817) dopo il 1807; per ultimo a destra ancora un ritratto eseguito dal Fabre al mercante Ferrandy, francese residente a Firenze nel 1793; nella fila più alta ancora tre ritratti, una coppia di fanciulle con gran cappelli di paglia dai nastri verdi, una giovinetta sullo sfondo di un una veduta della città di Dresda, di gusto tipicamente biedermeier, ed un severo ritratto di un giovane francese degli anni della Rivoluzione, che ricorda analoghi dipinti del David. In basso sulla sinistra un piccolo acquerello d’interno che raffigura un ambiente del Palazzo d’Inverno di San Pietroburgo.

***

Study:

Two rooms can be entered from the gallery: the library to the left and the study to the right. The movement towards the study is emphasized by the changing color scheme from white and gold to the predominant green of the walls combined with the red of the curtains.

An element of continuity between the two environments is given by the long gallery, a structure designed by the architect Lizzani to hold a part of Praz’s extensive library. It can be accessed via a staircase from the study, surmounted by paintings of military subjects, swords, and musical instruments decorated with fantastic dragon heads. At the foot of the stairs there is a painting of the great hall of the Palazzo Ricci where Praz lived for over thirty years before moving to Palazzo Primoli. It was painted in 1965 by Sergio De Francisco, and it is interesting to note that many of the objects shown in the picture are found in this room, including a desk or table in the center, as well as in the other rooms of the house. The same Sergio De Francisco painted the portrait of Praz on the wall of the studio, on the left as you enter.

Below the balcony, among some “conversation pieces” paintings, something that might be called “a collection within a collection.” There are numerous wax images of martyrs and saints, nobles and warriors, queens and princesses, pairs of plates, and classical portraits dating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, which interrupt for a moment the strict chronological order which the furniture of the house follows. The waxes, which the Professor collected passionately and almost morbidly into his old age, are realistic in the extreme; more than seventy of these objects are scattered throughout the house. The core of the wax collection is here below the balcony.

On the wall behind the desk, a fine French piece adorned with bronze, is a small picture gallery of nine paintings. There are three Italian landscapes in the central row and below that three portraits: the first one of the well-known Frenchman François-Xavier Fabre (1766-1837) made by Foscolo during his stay in Florence, of which several versions are known; the second is of Teresa Pikler, wife of Monti, shown in the garden of the Villa Borghese Lake, painted by Charles Labruzzi (1747-1817) after 1807; and at far right a portrait of the merchant Ferrandy Fabre, a Frenchman living in Florence in 1793. The top row of the small gallery are three more portraits, the first showing two girls with green-ribboned straw hats, the next a young girl with a view of Dresden in the background in typical Biedermeier style, and the third a stern portrait of a young French woman in the year revolution, reminiscent of similar paintings by David. Below on the left is a small watercolor depicting an interior room of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg.

la collezione di cere

The collection of waxes

Mario Praz in età matura ritratto da Sergio De Francisco

Mario Praz in maturity, portrait by Sergio De Francisco

la scrivania del Professore

Praz’s desk

Ritratto di Foscolo di François-Xavier Fabre; accanto: Ritratto di Teresa Pikler, moglie del Monti, nel giardino del Lago a Villa Borghese eseguito da Carlo Labruzzi

Portrait of Foscolo by François-Xavier Fabre; next: Portrait of Teresa Pikler, wife of Monti, in the garden of the Villa Borghese Lake painted by Charles Labruzzi

sotto il busto: dipinto raffigurante gli interni di Palazzo Ricci, opera di Sergio De Francisco

Below the bust: painting of the interior of the Palazzo Ricci, by Sergio De Francisco

il vaso di fiori sul tavolino al centro della stanza è in realtà fatto di conchiglie dipinte.

The vase of flowers on the coffee table in the center of the room is actually made of painted shells.

Trackbacks per le News